New Taxon of Giant Tortoise Discovered in Galápagos Islands

New DNA analysis of century-old tortoise bones published this week in Heredity, one of the world’s leading journals of genetics, contained a startling revelation: the extant Giant Tortoise species on San Cristóbal Island in Galápagos represents a genetically distinctive and undescribed group of organisms, or “taxon,” new to science. The San Cristóbal Giant Tortoise (Chelonoidis chathamensis) described over a century ago is now likely an extinct species.

New DNA analysis of century-old tortoise bones published this week in Heredity, one of the world’s leading journals of genetics, contained a startling revelation: the extant Giant Tortoise species on San Cristóbal Island in Galápagos represents a genetically distinctive and undescribed group of organisms, or “taxon,” new to science. The San Cristóbal Giant Tortoise (Chelonoidis chathamensis) described over a century ago is now likely an extinct species.

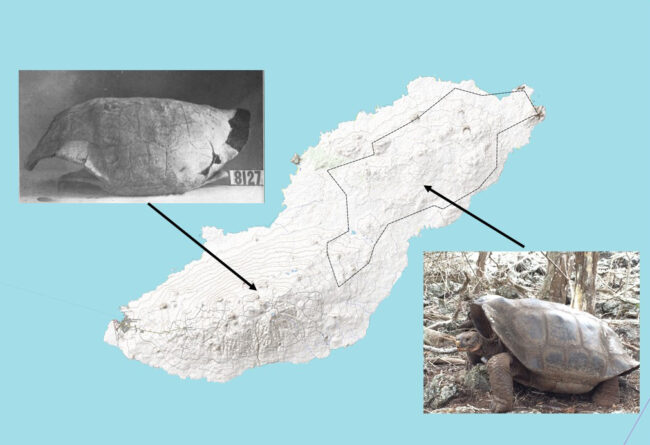

Until now, it has been presumed that the tortoises living on San Cristóbal belonged to a single species, C. chathamensis, which was described on the basis of bones and shells collected in a cave during a 1906 California Academy of Sciences expedition to the southwestern highlands of the island. That expedition never reached the northeastern lowlands of San Cristóbal where tortoises currently live.

However, researchers from University of Newcastle, Yale University, Galápagos Conservancy, and other institutions extracted DNA from these bones and made a remarkable discovery: The DNA does not match that of the tortoises currently inhabiting the island.

This means that:

1) The 8,000 tortoises living on San Cristóbal today may not be rightly called C. chathamensis at all, since they are another taxon (or lineage) entirely that has no formal description or scientific name;

2) The taxon that the name C. chathamensis belongs to from the San Cristóbal highlands is almost certainly extinct;

and 3) San Cristóbal Island had not one but two different taxa of tortoises living together — one in the highlands and one in the lowlands, each likely with different nesting areas — until the extinction of the highlands species in the middle of the 20th century.

The authors are currently working to recover more DNA from the extinct taxon to clarify the taxonomic status of the San Cristóbal tortoises and better understand how the current living species is related to the extinct one. It seems likely that there were two species on San Cristóbal, not one, and if this is the case, the name of C. chathamensis should be assigned to the extinct species, and the extant taxa should be given a new name.

San Cristóbal Island consists of two parts that, during times of high sea levels millions of years ago, may have been separate islands, each likely with its own tortoise species. Once sea levels dropped, the two islands merged, as perhaps did their tortoises. Today, the southwestern highlands section, where tortoises once flourished but were killed off by whalers and early-twentieth-century settlers, is moist and lushly vegetated. The northeastern section, where tortoises currently live, is lower and more arid.

A recent Galápagos Conservancy-Galápagos National Park Directorate joint expedition estimated 6,000 to 8,000 giant tortoises on San Cristóbal, recovering rapidly from a low of 500–700 individuals in the 1970s thanks to the cessation of poaching and removal of goats.

The full publication, “A new lineage of Galapagos giant tortoises identified from museum samples,” can be found here.